Celebrities and social climbers collect Warhol but what did Warhol collect?

“Keep the coffee tins—aluminum might go up!”

“Keep the batteries—copper might go up!”

According to Bob Colacello, who worked with Warhol as the editor of Interview magazine and as his unofficial sales agent, “Warhol was not a collector; he was a hoarder.”

When Colacello worked with Warhol, a portrait started at $25,000; they’re worth millions today. The key was to lure socialites to commission them. “Pretty society women wanted their portraits done but it was their stockbroker/private equity husbands who were going to pay, so Andy would tell me to play up my Republican side,” says Colacello.

“A client once paid Warhol with an large, uncut Colombian emerald.”

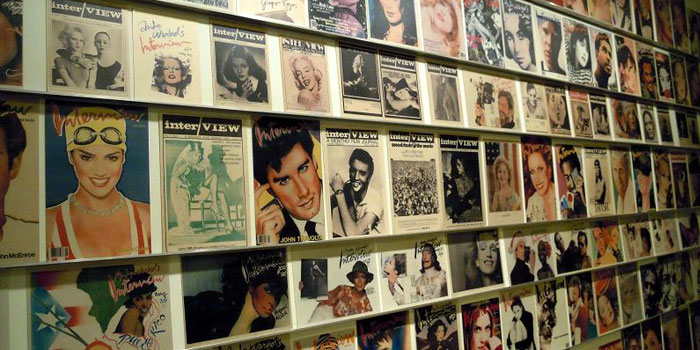

It was society “walker” Jerome Zipkin who amped Warhol’s fortunes. He gave subscriptions to Interview to all of his ladies—party circuit regulars like Betsey Bloomingdale, Nan Kempner, and Carolyn Roehm. The magazine, which was launched in 1968 was shuttered this month. It had switched from covering film criticism to interviewing famous people and became the definitive pop journal of downtown Manhattan. Society types tripped over each other to land on the magazine’s cover. Colacello pocketed a small commission for each portrait he sold. Once, when a client paid for her portrait with a large, uncut Colombian emerald in lieu of cash, Warhol offered Colacello his own portrait as commission. “He told me he knocked $3,000 of the price,” says Colacello.

Despite Warhol’s legendary tightfistedness, Colacello managed to amass a small collection of his work. “I wish I hadn’t sold because it kept going up in value. Still, it did buy me a place in East Hampton.”

Today, buying a Warhol is like buying shares in Microsoft. Solid, not sexy. But that’s where the similarities end.

“Art investing is a high-stakes game.”

Art investing is a high-stakes game. Many people think they can clean up but survivorship bias distorts market returns. For every Frank Auerbach painting bought for $1.1 million in 2005 and sold for $2.3 million in 2006, there are hundreds of artists whose careers die a silent death. We only ever hear about the winners.

Unlike the major stock markets, the art market is insular and lacks transparency. Amazon and eBay may sell fancy pictures but the real big money deals are typically made privately. Price manipulation is the name of the game because dealers are expected to nurture artists’ careers. To do so, collectors are discouraged from selling works in the open market, and if they do so, gallery owners will bid up prices to keep the mystique alive. Because buying art is aspirational, not being able to sell a piece at auction could be career-ending for an emerging artist.

Liquidity is another issue. Even more than in real estate, sometimes there’s absolutely no demand for a work of art. Like other ‘alternative’ investments, returns from art are all over the map. However, due to high transaction and commission costs, realistic net returns over a 5-year holding period hover between 1%-5%. Not great shakes.

“Being an art collector raises your social capital.”

So why invest in art? Well, it’s pretty. What you lose in financial return you potentially gain in everyday pleasure and social cachet. It’s doubtful that gazing at your quarterly investment statement provides the same spiritual uplift. Being an art collector also raises your social capital. There are art openings, cocktail parties, meet-the-artist fetes and so forth. It’s a special club—particularly at the upper echelons—that provides a global passport to hobnobbing.

But if the art market is a little too rich for you, then follow Warhol and invest in physical commodities. Gold, aluminum, copper, iron…demand is bound to pick up one day.

*Photo: Covers of “Interview” (magazine) — displayed in the Andy Warhal Museum, Pittsburgh, PA.